Why Trade Deficits Aren’t Bad—and Surpluses Aren’t Always Good

2025 · discussion

Created: November 18, 2025

Author: Pattawee Puangchit

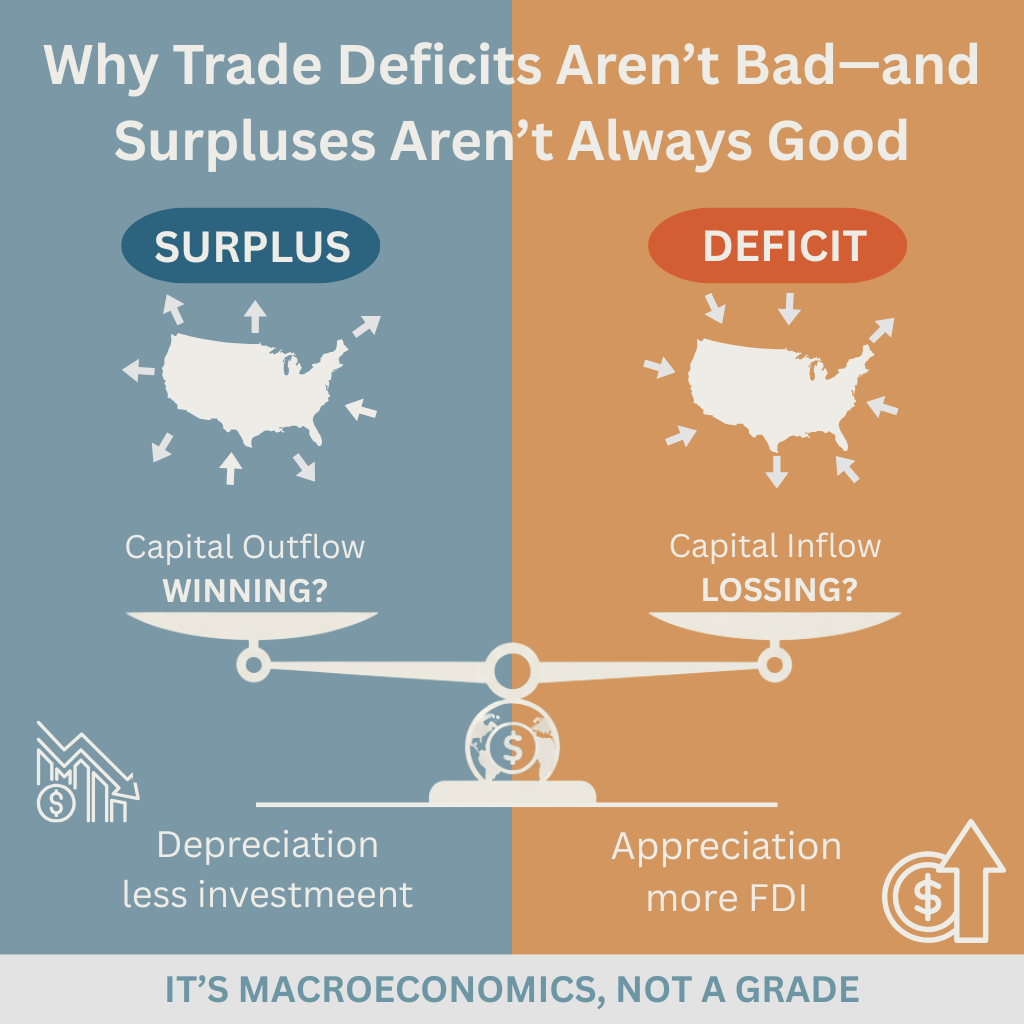

The trade balance often gets treated like a scoreboard: surplus = winning, deficit = losing. But economies aren’t built on simple wins and losses. This is one of the most misunderstood numbers we debate, and the real meaning sits underneath the surface.

This blog will walk through what a deficit or surplus actually signals, and why the truth is more complex than “good” or “bad.”

Trade Deficit

-

What’s a trade deficit?

A trade deficit doesn’t mean a country is “losing money.” When a country imports more than it exports, many assume money is leaking out of the economy — but that’s not how international trade works. A trade deficit also represents capital inflow.

You receive goods today, and foreigners invest their money in your country. They don’t take your currency and disappear with it — instead, they usually reinvest it back into your economy by purchasing:

- stocks

- bonds

- real estate

- business assets

A trade deficit isn’t inherently problematic — its meaning depends on the underlying factors. It could reflect weakness, but it may just as well indicate strong spending, high investment demand, or a trusted currency.

📘 Key Economic Terms

- Trade deficit

- This occurs when a country buys more from another country than it sells.

- For example, if Thailand imports $5B from the U.S. but exports only $3B, Thailand runs a trade deficit with the U.S.

- Capital inflow

- This means foreign money flows into a country — typically because foreigners are purchasing bonds, stocks, real estate, or business assets.

- Simply put, you receive goods today, and foreigners invest their money in return.

-

When deficits become harmful?

A deficit is harmful when it signals deeper structural issues, rather than a normal part of economic growth. Here are some key indicators.

1. Excessive borrowing for consumption

A trade deficit becomes risky when a country is importing more not because its economy is strong, but because it is borrowing heavily to sustain its lifestyle.

When imports are funded by debt instead of income, the deficit becomes a red flag:

the country is living beyond its means, and the bills will eventually come due.Why this is harmful

- Debt grows faster than the country’s ability to repay.

- Foreign investors lose confidence and withdraw funds.

- Currency weakens, making repayment even more expensive.

- The economy may collapse if lenders no longer trust the borrower.

How to tell if a deficit is debt-driven

- Government borrows from abroad to cover regular spending.

- Households use easy credit to buy imported goods.

- Imports remain high even when economic growth slows.

- External debt rises faster than national income.

Real-world examples

- Latin American Debt Crisis (1980s): Heavy foreign borrowing → collapse, inflation, and IMF rescues.

- Greek Debt Crisis (2009–2018): Public debt surged → investors lost trust → deep recession and austerity.

📈 Key Economic Terms

- External debt

— money borrowed from foreign lenders. - Debt-financed deficit

— a deficit financed by borrowing instead of productive economic activity.

2. Sudden stop in capital inflows

Some economies rely heavily on foreign investment to finance their deficits. When investors suddenly withdraw — known as a sudden stop — the country can no longer afford its imports or roll over its debt.

The economy can collapse rapidly.

Why this is harmful

- Currency crashes as investors flee.

- Imports become unaffordable almost overnight.

- Banks run out of foreign exchange.

- Businesses fail due to a lack of credit.

How to tell if a country is vulnerable

- A large portion of financing comes from short-term foreign investors.

- Banks and firms borrow heavily in foreign currency.

- Foreign reserves are low relative to imports.

Real-world example

- Asian Financial Crisis (1997)

Sudden capital flight → currency collapses → deep regional recession.

3. Weak currency + weak institutions

A trade deficit is more dangerous when combined with political instability, unpredictable economic policies, or weak rule of law.

Foreign investors demand higher returns to compensate for risk. If confidence wanes, currencies can collapse and inflation can soar.

Why this is harmful

- Investors avoid risky environments → capital outflows increase.

- A weak currency makes imports expensive, worsening inflation.

- Governments struggle to stabilize the economy.

- Crisis cycles repeat due to lack of institutional credibility.

Warning signs

- Sudden political shifts or policy reversals.

- Central bank unable to control inflation.

- Frequent government interventions in markets.

- Persistent loss of investor confidence.

Real-world examples

- Argentina’s repeated financial crises

Chronic instability → recurring currency collapses. - Turkey’s ongoing currency crisis (2018–present)

Unpredictable policy → currency meltdown → inflation.

Bottom line

A deficit is harmful only when it reflects debt stress, sudden capital flight, or institutional fragility — not just because imports are high.

-

When deficits are normal — or even beneficial?

Many strong economies run deficits during periods of growth and modernization.

1. High investment and rising productivity

Countries import machinery, technology, and industrial inputs when upgrading their economies. These imports boost future productivity and income.

A deficit here reflects modernization, not weakness.

Why this is healthy

- Imports expand production capacity.

- New technology promotes long-term growth.

- Firms become more competitive internationally.

Real-world pattern

- ASEAN economies increasing machinery imports during industrial upgrading:

ASEAN Economy

2. Attractive investment environment

Countries with strong institutions attract foreign capital. Foreigners invest heavily → money flows in → a deficit naturally arises.

This is a sign of confidence, not vulnerability.

Why this is healthy

- Stable political institutions attract long-term investors.

- Foreign investment stimulates innovation and business growth.

- Currency remains strong due to investor demand.

Real-world pattern

- Persistent U.S. trade deficits due to global demand for American assets:

Economy of the United States

3. High household purchasing power

When people earn more, they buy more — including imported goods. A deficit in this case reflects rising living standards.

Why this is healthy

- Households have high incomes.

- Consumer demand supports overall growth.

- Imports complement, rather than replace, domestic production.

Real-world pattern

- Australia runs deficits despite high incomes and living standards:

Economy of Australia

Bottom line

A deficit is healthy when it arises from strong investment, strong institutions, or strong consumers — not from debt or instability.

Trade Surplus

-

What’s a trade surplus?

A trade surplus occurs when a country exports more than it imports. It may look automatically positive, but it also reflects capital outflow — money leaving the country to acquire foreign assets. A surplus can come from strong exports, but it can also appear when households and firms spend too little or see few investment opportunities at home.

In those cases, the surplus is not a sign of strength. Imports fall not because exporters are booming, but because domestic spending is soft or constrained. The number looks “good,” but the mechanism underneath is weak.

- export earnings

- foreign asset purchases

- outward capital flows

📘 Key Economic Terms

- Trade surplus

When a country sells more abroad than it buys. - Capital outflow

Money leaving the country to acquire foreign assets. Surpluses naturally generate capital outflow.

-

When surpluses become harmful?

A surplus becomes problematic when it reflects domestic weakness rather than actual export strength.

1. Weak domestic spending

A surplus can increase when households and firms spend too little. Imports fall not because exports surge, but because the domestic economy is weak. When people delay purchases, reduce consumption, or avoid investment, the surplus rises for reasons unrelated to competitiveness.

When this pattern persists, the surplus becomes a reflection of domestic fragility. Firms face slow demand, investment is delayed, and growth becomes overly reliant on foreign sales because the home market is not absorbing enough. The number may look “strong,” but the engine beneath it is weak.

Why this is harmful

- sluggish consumption weakens growth

- firms delay investment

- living standards stagnate

How to tell when this is happening

- sluggish retail sales

- broad-based declines in consumer-goods imports

- persistent underinvestment by firms

Real-world example

- During periods of fiscal austerity in parts of Europe, imports fell because spending was reduced, not because exports suddenly boomed. European austerity

2. Aging population and high saving

Older economies tend to save more and spend less. Lower spending reduces imports and pushes the surplus higher for demographic reasons rather than competitive strength. When a society ages, households prioritize saving, consumption slows, and imports naturally decline even if exports remain unchanged.

This creates a surplus that reflects long-term structural drag. Over time, weaker domestic consumption limits wage growth, shrinks the labor force, and forces the economy to rely heavily on external demand to sustain growth. The surplus grows, but the underlying growth engines weaken.

Why this is harmful

- long-term drag on domestic consumption

- shrinking labor force

- fewer domestic growth engines

How to tell when demographics drive the surplus

- rising old-age dependency ratio

- slow or negative growth in household spending

- increasing reliance on exports for overall growth

Real-world example

- Japan combines high saving and an aging population with persistent surpluses. Economy of Japan

3. Limited investment opportunities at home

A surplus can also grow when businesses see fewer attractive projects at home and instead invest abroad. When businesses lack confidence in the domestic economy, they send capital outward, slowing innovation and weakening productivity growth at home.

The surplus becomes a reflection of missed opportunities. Instead of upgrading local industries, capital flows outward in search of higher returns, leaving the domestic economy with stagnant investment and weaker long-term growth prospects.

Why this is harmful

- innovation slows

- productivity growth weakens

- capital leaves rather than upgrading local industries

How to tell when this is happening

- stagnant private investment despite high savings

- low business-confidence surveys

- productivity growth falling behind peers

Real-world example

- In parts of Southern Europe after the euro crisis, surpluses increased as domestic investment collapsed and savings were pushed abroad. European debt crisis

Bottom line

A surplus is not always a strength. Sometimes it reflects weak demand, aging demographics, or limited investment capacity rather than true competitiveness.

-

When surpluses are good?

A surplus is healthy when it arises from competitiveness, productivity, or well-managed saving behavior.

1. Strong export competitiveness

Countries with high-performing industries naturally generate surpluses because the world wants their goods and services. When firms produce high-value, reliable, or technologically sophisticated products, exports rise consistently, creating a surplus driven by capability rather than weakness.

In these cases, the surplus reflects an economy that competes effectively worldwide. Firms expand, wages rise, and the export base supports domestic growth rather than replacing it.

Why this is healthy

- stable export revenues

- strong industrial capabilities

- diversified export markets

Signs of competitiveness-driven

- rising share of exports in high-value sectors

- diverse trading partners

- surplus paired with solid wage growth and investment

Real-world examples

- Germany’s manufacturing strength Economy of Germany – Exports

- South Korea’s semiconductor industry Semiconductor industry in South Korea

- Singapore’s high-tech and services hub Economy of Singapore – Industries

2. High productivity + disciplined saving

Well-managed, productive economies often save more than they invest at home and channel the surplus into foreign assets. This strengthens the national balance sheet, builds resilience in crises, and allows the country to earn stable income from abroad.

When productivity and disciplined saving work together, the surplus reflects long-term strategic positioning rather than domestic weakness.

Why this is healthy

- stronger net foreign asset position over time

- more resilience in crises

- ability to earn income from abroad

How to tell this is the good kind of surplus

- persistent surplus with low external debt

- large, well-managed investment funds

- stable inflation and credible policy

Real-world example

- Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, built from resource income and high saving. Government Pension Fund of Norway

3. Upgrading into higher-value production

Economies that move into more advanced sectors often see exports grow faster than imports. As firms climb the value chain, produce more sophisticated goods, or expand into knowledge-intensive sectors, the surplus increases because the country is producing more value per worker.

This is the healthiest form of surplus — driven by structural change, stronger capabilities, and rising long-term potential.

Why this is healthy

- rising value-added per worker

- more sophisticated export basket

- stronger long-term growth potential

How to tell this is happening

- shift toward complex or technology-intensive exports

- rising R&D and innovation spending

- improving economic-complexity rankings

Real-world example

- China’s 2000s export boom, driven by movement into higher-value manufacturing. Economic history of the People’s Republic of China – Reform and growth

Bottom line

A surplus is healthy when it is backed by competitiveness, productivity, and structural upgrading, not when it is the side-effect of weak domestic demand.

The Real Point

The trade balance is not a scorecard. It’s simply the result of how a country saves, invests, produces, and interacts with global capital.

The idea that “deficit = bad” or “surplus = good” comes from treating a country like a household. But economies aren’t households — they’re open systems where money, goods, and investment constantly move across borders.

A trade number by itself won’t tell you if an economy is strong or weak.

You need the story behind the number — the saving, the investment, the capital flows, and the macro forces shaping them.

That’s where the real economics lives.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Pattawee Puangchit.(2025, November 18).Why Trade Deficits Aren’t Bad—and Surpluses Aren’t Always Good.Pattawee Puangchit.https://www.pattawee-pp.com/trade-talk/2025/trade-balance-discussion/.

@misc{puangchit2025why-trade-deficits-aren-t-bad-and-surpluses-aren-t-always-good,

title = { Why Trade Deficits Aren’t Bad—and Surpluses Aren’t Always Good },

author = { Puangchit, Pattawee },

howpublished = { Pattawee Puangchit | Personal Website },

year = { 2025 },

month = { Nov },

url = { https://www.pattawee-pp.com/trade-talk/2025/trade-balance-discussion/ }

}

trade-balance • international-trade • macroeconomics • explanation